Did the Hanging Gardens Ever Really Exist?

There is still much debate about the existence of the Hanging Gardens. The Hanging Gardens seem magical in a way, too amazing to have been real. Yet, so many of the other seemingly-unreal structures of Babylon have been found by archaeologists and proven to have really existed.

Yet the Hanging Gardens remains aloof. Some archaeologists believe that remains of the ancient structure have been found in the ruins of Babylon. The problem is that these remains are not near the Euphrates River as some descriptions have specified.

Also, there is no mention of the Hanging Gardens in any contemporary Babylonian writings. This leads some to believe that the Hanging Gardens were a myth, described only by Greek writers after the fall of Babylon.

A new theory, proposed by Dr. Stephanie Dalley of Oxford University, states that there was a mistake made in the past and that the Hanging Gardens were not located in Babylon; instead, they were located in the northern Assyrian city of Ninevah and were built by King Sennacherib. The confusion could have been caused because Ninevah was, at one time, known as New Babylon.

Unfortunately, the ancient ruins of Ninevah are located in a contested and thus dangerous part of Iraq and thus, at least for now, excavations are impossible to conduct. Perhaps one day, we will know the truth about the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Featured Video

Источники

- Браун, Джули (1994). «Ранние вагнеризмы Шенберга: атональность и искупление Артаксеркса». Кембриджский оперный журнал 6, вып. 1 (март): 51–80.

- Дик, Марсель (1990). “Введение в” Книгу висячих садов ” Арнольда Шенберга , соч. 15″. В исследованиях шенберговского движения в Вене и Соединенных Штатах: Очерки в честь Марселя Дика , под редакцией Анны Тренкамп и Джона Г. Зюсса, 235–39. Льюистон, Нью-Йорк: Меллен Пресс. ISBN 0-88946-449-9

- Домек, Ричард К. (1979). “Некоторые аспекты организации в” Книге висячих садов “Шенберга, опус 15”. Симпозиум музыки колледжа 19, вып. 2 (Осень): 111–28.

- Дюмлинг, Альбрехт (1981). Die fremden Klänge der hängenden Gärten. Die offentliche Einsamkeit der Neuen Musik am Beispiel von A. Schoenberg und Stefan George . Мюнхен: Киндлер. ISBN 3-463-00829-7

- Дюмлинг, Альбрехт (1995). “Öffentliche Einsamkeit: Atonalität und Krise der Subjektivität in Schönbergs op. 15”. В стиле одер Геданке? Zur Schönberg-Rezeption in Amerika und Europa , под редакцией Стефана Литвина и Клауса Фельтена. Саарбрюккен: Пфау-Верлаг.

- Дюмлинг, Альбрехт (1997): «Общественное одиночество: атональность и кризис субъективности в Опусе 15 Шенберга». В кн . : Шенберг и Кандинский. Историческая встреча , под редакцией Конрада Бёмера, 101-38. Амстердам: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-5702-047-5

- Эванс, Ричард (1980). . Темп: Ежеквартальный обзор современной музыки 132 (март): 35–36.

- Хунекер, Джеймс (1913). «Шенберг, музыкальный анархист, расстроивший Европу». New York Times (19 января): раздел журнала, часть 5, страница SM9, 4055 слов

- Лессем, Алан Филип (1979). Музыка и текст в произведениях Арнольда Шенберга: критические годы, 1908–1922 . Исследования в области музыковедения 8. Анн-Арбор: UMI Research Press. ISBN 0-8357-0994-9 (ткань); ISBN 0-8357-0995-7 ( PBK )

- Медисис, Франсуа де (2005). «Дариус Мийо и дебаты о политональности во французской прессе 1920-х годов». Музыка и письма 86, вып. 4: 573–91.

- Паффет, Деррик (1981). . Музыка и письма 62, вып. 3 (июль – октябрь): 404–406.

- Райх, Вилли (1971). Шенберг: критическая биография , пер. Лео Блэк. Лондон: Лонгман; Нью-Йорк: Praeger. ISBN 0-582-12753-X . Перепечатано 1981, Нью-Йорк: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-76104-1

- Шефер, Томас (1994). “Wortmusik / Tonmusik: Ein Beitrag zur Wagner-Rezeption von Arnold Schönberg und Stefan George”. Die Musikforschung 47, no. 3: 252–73.

- Шорске, Карл (1979). Fin-de-siècle Вена: политика и культура , первое издание. Нью-Йорк: Кнопф; Лондон: Вайденфельд и Николсон. ISBN 0-394-50596-4

- Смит, Гленн Эдвард (1973). « Книга Висячих садов Шенберга : анализ». DMA дисс. Блумингтон: Университет Индианы, 1973.

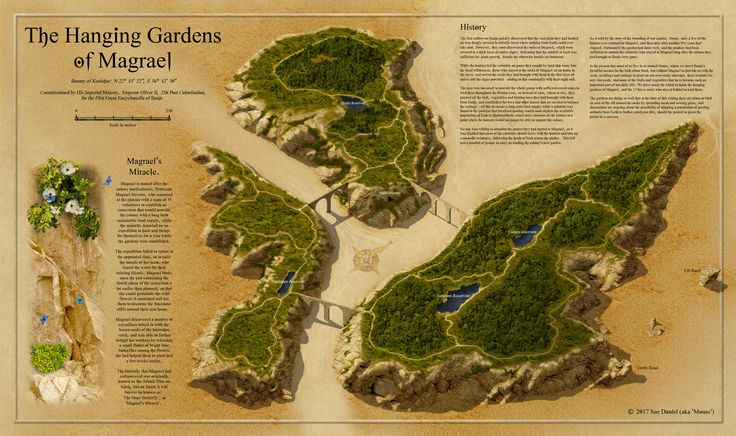

What are the hanging gardens of Babylon?

The city of Babylon was located near the city of Hillah in the Babil province of current-day Iraq.

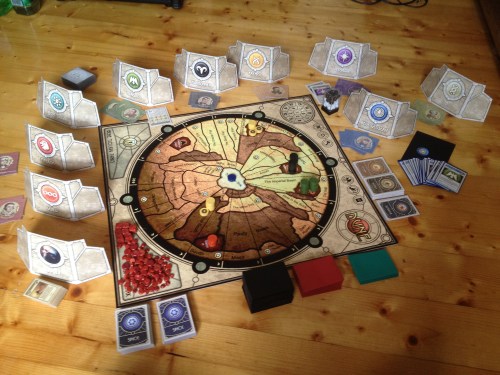

In this ancient city, there was a palace referred to as “The Marvel of Mankind.” It has been described that alongside this massive palace, tiered gardens were constructed that contained a variety of trees, bushes, and vines.

because of the way the gardens were positioned, it gave the impression that the Palace was sitting on top of a green mountain, while in fact, it was nothing but a garden consisting of mud bricks.Illustration of the hanging gardens of Babylon made in the 19th century / Wiki Commons

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

Hanging Gardens of Babylon history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

History of “Hanging Gardens of Babylon”

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Download the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Facts & Worksheets

Click the button below to get instant access to these worksheets for use in the classroom or at a home.

Download This Worksheet

This download is exclusively for KidsKonnect Premium members!To download this worksheet, click the button below to signup (it only takes a minute) and you’ll be brought right back to this page to start the download!Sign Me Up

Already a member? Log in to download.

Edit This Worksheet

Editing resources is available exclusively for KidsKonnect Premium members.To edit this worksheet, click the button below to signup (it only takes a minute) and you’ll be brought right back to this page to start editing!Sign Up

Already a member? Log in to download.

Nebuchadnezzar II and Babylon

The city of Babylon was founded around 2300 BCE, or even earlier, near the Euphrates River just south of the modern city of Baghdad in Iraq. Since it was located in the desert, it was built almost entirely out of mud-dried bricks. Since bricks are so easily broken, the city was destroyed a number of times in its history.

In the 7th century BCE, Babylonians revolted against their Assyrian ruler. In an attempt to make an example of them, Assyrian King Sennacherib razed the city of Babylon, completely destroying it. Eight years later, King Sennacherib was assassinated by his three sons. Interestingly, one of these sons ordered the reconstruction of Babylon.

It wasn’t long before Babylon was once again flourishing and known as a center of learning and culture. It was Nebuchadnezzar’s father, King Nabopolassar, that liberated Babylon from Assyrian rule. When Nebuchadnezzar II became king in 605 BCE, he was handed a healthy realm, but he wanted more.

Nebuchadnezzar wanted to expand his kingdom in order to make it one of the most powerful city-states of the time. He fought the Egyptians and the Assyrians and won. He also made an alliance with the king of Media by marrying his daughter.

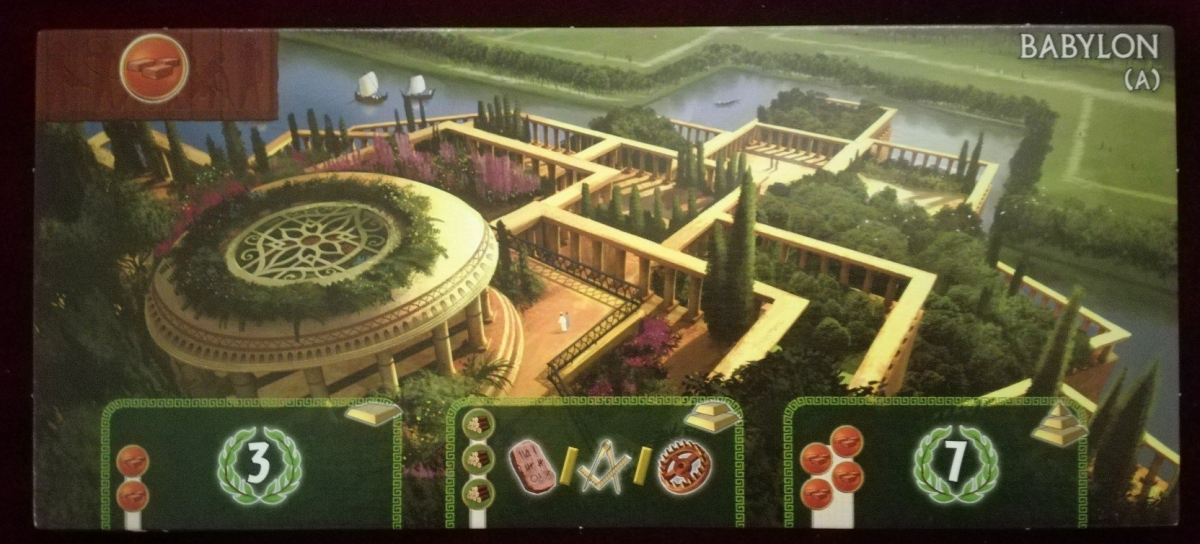

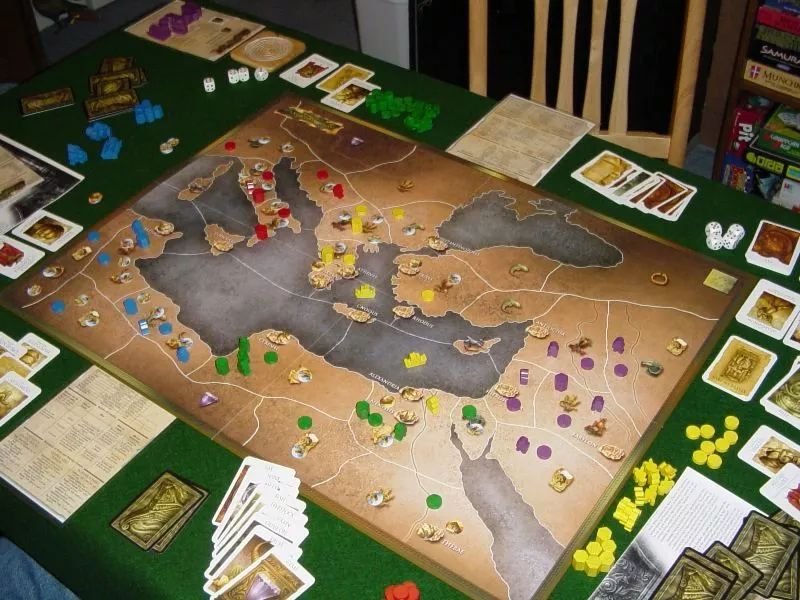

With these conquests came the spoils of war to which Nebuchadnezzar, during the course of his 43-year reign, used to enhance the city of Babylon. He built an enormous ziggurat, the temple of Marduk (Marduk was Babylon’s patron god). He also built a massive wall around the city, said to be 80 feet thick, wide enough for four-horse chariots to race on. These walls were so large and grand, especially the Ishtar Gate, that they too were considered one of the Seven Ancient Wonders of the World — until they were bumped off the list by the Lighthouse in Alexandria.

Despite these other awesome creations, it was the Hanging Gardens that captured people’s imagination and remained one of the Wonders of the Ancient World.

Archaeological Theories

Recent archaeological digs at Babylon have unearthed a major palace, a vaulted building with thick walls (perhaps the one mentioned by Greek historians), and an irrigation well in proximity to the palace. Although an archaeological team surveyed the palace site and presented a reconstruction of the vaulted building as being the actual Hanging Gardens, accounts by Strabo place the Hanging Gardens at another location, nearer the Euphrates River. Other archaeologists insist that since the vaulted building is thousands of feet from the Euphrates, it is too distant to support the original claims even if Strabo happened to be wrong about the location. The latter team reconstructed the site of the palace, placing the Hanging Gardens in a zone running from the river to the palace. Interestingly, on the banks of the Euphrates, a newly discovered, immense, 82-foot thick wall may have been stepped to form terraces like those mentioned by the ancient Greek sources.

Состав

Хотя 15 стихотворений не обязательно описывают историю или следуют линейному развитию, общие темы можно сгруппировать следующим образом: описание рая (стихотворения 1 и 2), пути, по которым влюбленный достигает своей возлюбленной (стихи 3 –5), его страсти (стихи 6–9), пик времени, проведенного вместе (стихи 10–13), предчувствие (стих 14) и, наконец, любовь угасает, и Эдема больше нет (стих 15).

Первая строка каждого стихотворения (Оригинал на немецком языке) Примерный английский перевод 1 Unterm Schutz von dichten Blättergründen Под тенью толстых листьев 2 Hain in Diesen Paradiesen Рощи в этом раю 3 Als Neuling trat ich ein in dein Gehege Как новичок, я вошел в ваш вольер 4 Da meine Lippen reglos sind und brennen Потому что мои губы неподвижны и горят 5 Saget mir auf welchem Pfade Скажи мне, на каких путях 6 Jedem Werke bin ich fürder tot Ко всему прочему я отныне мертв 7 Angst und Hoffen wechselnd sich beklemmen Страх и надежда попеременно угнетают меня 8 Wenn ich heut nicht deinen Leib berühre Если я сегодня не прикоснусь к твоему телу 9 Streng ist uns das Glück und spröde Строгость к нам – счастье и хрупкость 10 Das schöne Beet betracht ich mir im Harren Я смотрела на красивую пока ждала 11 Als wir hinter dem beblümten Tore Как мы за цветущими воротами 12 Wenn sich bei heilger Ruh in tiefen Matten Если это со священным покоем в глубоких циновках 13 Du lehnest wide eine Silberweide Вы прислоняетесь к белой иве 14 Sprich nicht mehr von dem Laub Больше не говори о листве 15 Wir bevölkerten die abend-düstern Lauben Мы заняли мрачные ночи аркады

The Hanging Gardens of Nineveh?

Following a recent investigation, Oxford University Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley has argued that the Hanging Gardens were not built by King Nebuchadrezzar II in Babylon at all, but in Nineveh by the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (r. 704-681 B.C.). Her thesis relies on the annals of his reign, which have been found inscribed on prism-shaped stones. In one the king boasts of the extensive monument-building he undertook: “I raised the height of the surroundings of the palace to be a Wonder for all peoples . . . A high garden imitating the Amanus mountains I laid out next to it with all kinds of aromatic plants.”

With its reference to wonder and height, the passage echoes many of the key aspects attributed to the Hanging Gardens. Just as classical writers referred to Babylon’s king imitating the landscape of Persia, Sennacherib’s annals detail the gardens’ imitation of Mount Amanus, a range in the extreme south of modern-day Turkey.

A relief from the time of Sennacherib’s grandson, Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 B.C.), depicts gardens with trees distributed across a slope topped by a pavilion. Water flows from an aqueduct to feed a series of channels filled with fish. The theory that this Ninevan pleasure park could well have been the famed Hanging Gardens is bolstered further by Sennacherib’s reputation for engineering innovation. He declared himself to be of “clever understanding.” The archives of his reign abound with references to ingenious irrigation systems, and some historians credit him with the invention of the Archimedes water screw. Archaeologists have also found an aqueduct system, built during his reign from two million blocks of stone, that brought water to the city across the Jerwan valley. (See “extremely rare” Assyrian reliefs discovered in a canal system near ancient Nineveh.)

The Jerwan structure lies on the route to Alexander the Great’s decisive battle with the Persians, at Gaugamela, in 331 B.C. Dalley argues that it is likely Alexander saw the aqueduct as he passed Nineveh. His inquiries into the sophisticated water systems and gardens of that city seeded the story of the Hanging Gardens, which scholarly confusion then misattributed to Babylon. If the theory is true, it would solve a great archaeological mystery, and leave few in doubt that the Hanging Gardens of Nineveh were a wonder indeed.

The elusive gardens

Apart from Babylon, all the monuments on Philo’s bucket list lie in or near the eastern Mediterranean, well within the Hellenist sphere of influence. The Hanging Gardens, however, are an eastern outlier, “a long journey to the land of the Persians on the far side of the Euphrates.”

When Philo wrote those words, Babylon, and the Persians, had been subdued a century before, by Alexander the Great, who had died in Babylon in 323 B.C. Despite the expansion of Greek culture eastward into Central Asia with Alexander’s armies, Babylon and its famed monuments would have struck Philo’s readers as highly exotic and remote. (Discover the true story of Semiramis, the legendary queen of Babylon.)

The ingenious Hanging Gardens, Philo writes, were laid out on a large platform of palm beams raised up on stone columns. This trellis of palm beams was covered with a thick layer of soil and planted with all kinds of trees and flowers, a “labor of cultivation suspended above the heads of the spectators.”

Aside from its hanging appearance, the gardens’ wondrous nature lay, according to Philo, partly in their variety: “All kinds of flowers, whatever is the most delightful, agreeable and pleasant to the eyes, is there.” Their system of irrigation also inspired wonder: “Water, collected on high in numerous ample containers, reaches the whole garden.”

Historians can draw on a wealth of later classical writers who reference the gardens. The first-century B.C. geographer Strabo and historian Diodorus Siculus both described the gardens as a “wonder.” Diodorus, a Greek author from Sicily, left one of the most detailed descriptions of the gardens as part of his monumental 40-volume history of the world, Bibliotheca historica. Like Philo, he detailed an elaborate system of supporting “beams”: These consisted of “a layer of reeds laid in great quantities of bitumen. Over this is laid two courses of baked brick, bonded by cement and as a third layer a covering of lead, to the end that the moisture from the soil might not penetrate beneath.” These layers, according to Diodorus, rose in ascending tiers. They were “thickly planted with trees of every kind that, by their great size or other charm, could give pleasure to the beholder,” and were irrigated “by machines raising the water in great abundance from the river.” (Babylon was the jewel of the ancient world.)

if(typeof __ez_fad_position!=’undefined’){__ez_fad_position(‘div-gpt-ad-listerious_com-banner-1-0’)};2. Who built the hanging gardens of Babylon?

The most popular version is that the most powerful and longest-reigning monarch of the Neo-Babylonian empire built the hanging gardens of Babylon.

His name was Nebuchadnezzar II and he reigned over the empire from 605 until 562 B.C. This means that if the story is correct, the hanging gardens of Babylon would have been built in this period.

The Bible doesn’t have any good stories about him. It refers to Nebuchadnezzar II regarding:

- His conquest of Judah.

- The destroyer of Solomon’s Temple.

- The initiator of the Babylonian captivity in which numerous Jewish people were held captive in Babylon.

Nevertheless, regardless of his track record, he is believed to be responsible for one of the 7 wonders of the ancient world.Ishtar gate of Babylon built by Nebuchadnezzar II / Source

if(typeof __ez_fad_position!=’undefined’){__ez_fad_position(‘div-gpt-ad-listerious_com-leader-2-0’)};5. Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon even exist?

Altogether there are only 5 written mentions of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon which are available today.

Here’s an overview:

Josephus – A Roman-Judea historian who was the first to make mention of the gardens in 290 B.C. He is the only one who claims Nebuchadnezzar II built the gardens, but then again, he got his information directly from a Babylonian priest named Berossus.

Diodorus Siculus – Ancient Greek historian who ascribed the gardens to a Syrian king and that the gardens were irrigated by the Euphrates River.

Quintus Curtius Rufus – A Roman historian who got his information from Diodorus, but added that the gardens were located on top of a citadel.

Strabo – A Greek geographer and historian who mentioned the irrigation system used an Archimedes’ screw which would have made it possible for water to be pumped up to water the top tiers of the gardens.

Philo of Byzantium – Confirms the writings of Strabo about the ancient water pump system and praises its ingenuity.

While there aren’t numerous sources, there are still enough sources to believe that the gardens did in fact exist.How the City of Babylon and hanging gardens could have looked like / Wiki Commons

if(typeof __ez_fad_position!=’undefined’){__ez_fad_position(‘div-gpt-ad-listerious_com-large-mobile-banner-1-0’)};4. Other theory of who built the hanging gardens of Babylon

While it’s generally accepted that Nebuchadnezzar II built the gardens for his wife, there is another theory.

This theory conceived by Stephanie Dalley, a British Ancient East expert, proposes that the gardens were built by the Assyrian King Sennacherib for his palace at Nineveh.

The arguments made are that Babylon, which literally translates to “Gates of the Gods” can refer to multiple cities in Mesopotamia and that there is actual evidence of an existing canal system that could provide the gardens at Nineveh with water.

Finally, there are also some inscriptions and wall reliefs mentioning and even depicting the gardens at Nineveh.

Are these the Hanging Gardens of Babylon or simply the gardens of Nineveh?

Without more conclusive evidence, the question will, unfortunately, remain an open one.Wall relief showing the gardens at the palace of Nineveh / Wiki Commons

Controversy

Stone tablets from Nebuchadnezzar’s reign give detailed descriptions of the city of Babylonia, its walls, and the palace, but do not refer to the Hanging Gardens. Today, some historians make the case that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon never actually existed.

Image of a “Hanging Garden” from an Assyrian tablet.

They stake their claims on the fact that the warriors in the army of Alexander the Great were amazed at the immense prosperity of the thriving city of Babylon and tended to exaggerate their experiences greatly. When the soldiers returned to their stark homeland, they had incredible stories to relate about the remarkable gardens, palm trees, and imposing buildings of rich and fertile Mesopotamia. This was, after all, the land of Nebuchadnezzar’s fabulous palace, the great Ishtar Gate, the legendary Tower of Babel, and other pyramid-like ziggurats. When all of these extraordinary architectural elements were combined together in the imagination of the poets, scholars, and historians of Ancient Greece, the result was another, although fictional, World Wonder. Others point to Assyrian tablets showing raised “hanging” gardens from the city of Nineveh, raising the possibility that the Babylonian gardens may be exaggerated, fanciful versions of what existed in another major Mesopotamian city.

Twentieth century archaeologists began collecting evidence about unsolved questions concerning the Hanging Gardens: What was their location? What kind of irrigation system did it have? What did the Hanging Gardens actually look like? These questions have yet to be fully answered.

The Hanging Gardens[]

Foot of the Gardens (Floor 1)

“King Dorgalua had these Hanging Gardens Built as a gesture of affection towards his queen, Vernotta”

- Leads to Floor 2

- Hidden Door to Floor 3 (19,9/8)

- Hidden Door to Floor 6 (5,12/12)

- (If returning by WORLD – there is also a shortcut to Floor 18)

The Serpent’s Spine (Floor 2)

“The sluice gates to the Hanging Gardens. Excess water was released here to control water levels in the gardens. Parts were build to work in aeternum”

Leads to Floor 4

“A statue of a god molded in pure gold once rested on this floor. It was stolen during the war.”

Leads to Floor 5

Echoes of Her Passage (Floor 4)

“A statue of a goddess molded in pure silver once rested on this floor. It was stolen during the war”

- Leads to Floor 7

- Hidden Door to Floor 8 (3,12/15)

“According to rumor, the waterway here was once lined with topaz stones”

Leads to Floor 8

The Verdant Stair (Floor 6)

“A steep stair facing north, thought to be for emergency use during an attack”

- Leads to Floor 7

- Hidden Door to Floor 10 (7,9/11)

“Black-haired entertainers from faraway lands once played and sang from morning till night”

Leads to Floor 9

Enraptured Dreams (Floor 8)

“A playroom designed by King Dorgalua himself for his son, born when Dorgalua was already well-on in years”

Leads to Floor 10

Hold High Your Cups (Floor 9)

“Here, during times of peace, the King would share wine with the knights who had fought for his throne”

- Leads to Floor 10

- Hidden Door to Floor 11 (15,13/24)

- Hidden Door to Floor 12 (15,5/18)

Halcyon Days (Floor 10)

“One of the King’s favorite parts of the gardens. How charming the swirling flower petals, how delicious the fruit, and how beautiful the maidens”

Leads to Floor 13

“The Hippogryph that served as the King’s steed in war was stabled here”

Leads to Floor 14

Vermillion Stair (Floor 12)

“This Corridor was used as a landing for shipments of food and other provisions to the gardens”

- Leads to Floor 15

- Hidden Door to Floor 16 (13,9/19)

Sounding of the Hours (Floor 13)

“Following the death of the Prince, the King sat long hours here before illness took him.”

- Leads to Floor 15

- Hidden Door to Floor 16 (12,14/27)

Faith and Devotion (Floor 14)

“Thinking that the Prince’s death had been his own doing, the King offered himself to the Gods hoping to do penance”

Leads to Floor 15

“After the Prince’s death, the Queen spent much of her time here, gazing at the stars”

Leads to Floor 17

Ebon Stair (Floor 16)

“This passageway used to lead to the uppermost level, but was closed when the Prince fell from here to his death”

- Leads to Floor 17

- Hidden Door to Floor 18 (4,1/4)

Ivory Stair (Floor 17)

“A passageway to the uppermost level. Here the Prince ascended to the next world, led by a heavenly host”

Leads to Floor 18

Twixt Heaven and Earth (Floor 18)

“The uppermost level of the Hanging Gardens. A flame burned here for 100 days in an offering that the Prince’s soul might find rest after his death”

Leads to “The Heart of the Gardens”

Earliest accounts

After much puzzling over Philo’s, Diodorus’s, and other first-century B.C. accounts of Babylon and its monuments, historians have traced the earliest written sources back to Greek scholars working during and just after the reign of Alexander the Great. Diodorus and Strabo, for example, both drew on accounts of Babylon from fourth-century B.C. writers such as Callisthenes, Alexander’s court historian and great-nephew of the philosopher Aristotle. Scholars believe that the passage in Diodorus’s Bibliotheca historica that describes the Hanging Gardens is derived from a work by a biographer of Alexander the Great, Cleitarchus, who was writing in the late fourth century B.C. His work has not survived but is known through allusions by other authors. The biography was a colorful and gossipy account of Alexander’s age.

Another important source of information on the gardens was written by a Babylonian priest named Berossus who lived in the early third century B.C. (soon after the time of Cleitarchus, and several decades before Philo). Judging by other accounts of his lost writings, Berossus seems to have introduced details about the gardens that inspired artists for centuries afterward, writing of high stone terraces lined with trees and flowers. Berossus also wrote that King Nebuchadrezzar II constructed the gardens in Babylon in honor of his wife, Amytis of Media, who longed for the lush mountain landscape of her native Persia. (Under king Cyrus the Great, Persia became the world’s first true empire.)

This romantic story has helped fix the gardens in the popular imagination. But historians are faced with a problem: All sources that reference a Babylonian garden remarkable for being suspended or tiered date from the fourth century B.C. at the earliest. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century B.C.— only a century after the time of Nebuchadrezzar—makes no mention of these remarkable gardens when describing Babylon in his Histories. Further dashing hopes that documentary evidence would shed light on the gardens, the texts that have been discovered from the time of Nebuchadrezzar’s reign contain no mention at all of any elevated gardens in the city.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon Facts

- The gardens were up to 75 feet high and it is thought that the plants tumbled down over a kind of pyramid-shaped stone structure.

- The whole thing looked like a mountain!

- To make the gardens, the King had to build really deep foundations.

- The Hanging Gardens were pretty heavy, made of stone pillars and slabs, dirt and plants, so the King needed to make sure it wouldn’t all collapse.

- Some people think that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were destroyed, perhaps by an earthquake or by war, but no one is sure.

- In fact, not everyone believes the Hanging Gardens ever actually existed. Some say they were just a legend.

- Although archaeologists have looked, no one has yet found any archaeological proof that they really did exist. All we have are ancient written descriptions of how they looked.

- The gardens were first written about by a priest called Berossus. He described high walkways, held up by stone pillars. He said there were plants and trees and it looked like a mountainous country. Other writers described the gardens similarly.

- Babylon was in a desert, so there wasn’t much water around. This meant that the Hanging Gardens needed their own watering system so the plants and trees got enough water. One theory is that there was a pump system to transport water to the top of the gardens – water that possibly came from the nearby Euphrates River. From the top, the water would cascade down over all the plants, trees and flowers.

- The gardens are considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World because of their architecture and design and the beautiful effect of tumbling exotic flowers and plants. They were also quite unique in being so green and vibrant in what was quite a dry place. A botanical garden like this was pretty unusual at the time!

- Some researchers think that the gardens weren’t even in Babylon at all, but near a city called Nineveh, which was further north than Babylon. Like so much about the gardens, this has not yet been proved.

- The city of Babylon itself also no longer exists. For a long time, it was believed to be the biggest city in the world. It was also the most famous city of the region called Mesopotamia.

- The name Babylon means ‘Gate of God’ or ‘Gate of the Gods’. There are many references to Babylon in the Bible.

x

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a

web browser that

supports HTML5 video

Facts for Kids

Question: Who were the gardens built for?

Answer: They were built for Queen Amytis, the wife of King Nebuchadnezzar.

Question: Can you visit the Hanging Gardens today?

Answer: No, they no longer exist.

Monumental confusion

The first-century A.D. Roman Jewish historian Josephus wrote that the gardens lay within Babylon’s main palace. During the first excavations of the ruins of Babylon, directed by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917, a robust, arched structure was unearthed in the northeast corner of the Southern Palace.

Koldewey believed that this was the very structure that had supported the famous gardens. It was made of carved stone, making it more resistant to moisture than mud brick. Its extremely thick walls would have been perfect for supporting the heavy superstructure. In addition, there was evidence of wells, which Koldewey assumed had formed part of the gardens’ irrigation system.

Today, however, most scholars agree that the building was probably a warehouse. Several storage jars were excavated from the site, but the strongest evidence is a cuneiform tablet unearthed there that dates to the time of Nebuchadrezzar II. The record contains details about the distribution of sesame oil, grain, dates, spices, and high-ranking captives. (This is how Koldewey and his team uncovered Nebuchadrezzar II’s vibrant Ishtar Gate.)

Koldewey’s excavation is most famous for revealing the foundations of a wondrous structure that really did exist: Babylon’s ziggurat, or stepped tower. A decade later, while British archaeologist Leonard Woolley was excavating the ancient Sumerian city of Ur to the southeast of Babylon, he noted regularly spaced holes in the brickwork of the ziggurat there. Might these be evidence of some kind of drainage or irrigation system supplying gardens rising up the face of the Ziggurat of Ur? Perhaps this kind of system, Woolley speculated, was later used to design the Hanging Gardens in Babylon. (Agatha Christie mended a broken heart through archaeology in Mesopotamia.)

Spurred, perhaps, by the lively public interest such a theory would awaken, Woolley embraced the theory. But archaeologists largely agree that his sober, initial assessment was correct: The holes were bored to enable the even drying of the brickwork during its construction.

Faced with this lack of documentary and archaeological evidence, some experts have opted for a radical reframing of the quest for the Hanging Gardens: What if they were not in Babylon at all? This wonder of the world could well be located in another city entirely.

This hypothesis is not as radical as it may appear at first: Greco-Roman sources that reference the Hanging Gardens tended to present historical detail interwoven with myth and legend, and their recounting of the history of great Mesopotamian civilizations often confused Assyria and Babylonia. Diodorus, for example, places Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, next to the Euphrates, although in fact the city stood on the banks of the Tigris.

In another passage Diodorus describes the walls of Babylon, detailing its rich depiction of animals, hunted by “Queen Semiramis on horseback in the act of hurling a javelin at a leopard, and nearby her husband Ninus, in the act of thrusting his spear into a lion.” No such hunting scene has been found in Babylon. It does, however, correspond closely with neo-Assyrian hunting reliefs engraved on the stone walls of the Northern Palace in Nineveh.

History

During the rule of the well-known king, Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.E.), the kingdom of Babylonia rose to prominence above the cities of Mesopotamia. However, Babylonian civilization did not reach the apex of its glory until the reign of Nabopolassar (625–605 B.C.E.), who began the Neo-Babylonian empire. His fabled son, Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 B.C.E.), the presumed builder of the legendary Hanging Gardens is said to have constructed them in order to win favor with his wife, Amyitis, who had been “brought up in Media and had a passion for mountain surroundings.”

Philo of Byzantium, thought by many to be the first to compile a list of the Seven Wonders of the World in the late second century B.C.E., raised the issue whether the plants in the Hanging Gardens were hydroponic. Philo noticed that plants were cultivated above ground, while the roots of the trees were embedded in an upper terrace of the garden rather than in the earth. This was certainly an advanced agricultural technique for the time, if true.

Strabo, the first century B.C.E. Greek historian and geographer, in Book 16 of his 17-book series, Geography (in the Middle East), described the geo-political landscape of the Hanging Gardens, as he did with much of the known world during the reigns of the first two Roman emperors, Augustus and Tiberius.

What Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Look Like?

It may seem surprising how little we know about the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. First, we don’t know exactly where it was located. It is said to have been placed close to the Euphrates River for access to water and yet no archeological evidence has been found to prove its exact location. It remains the only Ancient Wonder whose location has not yet been found.

According to legend, King Nebuchadnezzar II built the Hanging Gardens for his wife Amytis, who missed the cool temperatures, mountainous terrain, and beautiful scenery of her homeland in Persia. In comparison, her hot, flat, and dusty new home of Babylon must have seemed completely drab.

It is believed that the Hanging Gardens was a tall building, built upon stone (extremely rare for the area), that in some way resembled a mountain, perhaps by having multiple terraces. Located on top of and overhanging the walls (hence the term “hanging” gardens) were numerous and varied plants and trees. Keeping these exotic plants alive in a desert took a massive amount of water. Thus, it is said, some sort of engine pumped water up through the building from either a well located below or directly from the river.

Amytis could then walk through the rooms of the building, being cooled by the shade as well as the water-tinged air.